As demand for AI, cloud storage, and streaming services eats up more of Earth’s power grids and fresh water, tech giants and researchers are floating a radical solution: build data centers in space. WIRED reports that over half of current data center energy comes from fossil fuels, electricity demand for AI centers could rise by 165 percent by 2030, and companies like OpenAI, Bezos’s groups, and others are pushing the idea of orbiting data centers to tap solar power and sidestep terrestrial resource constraints. Meanwhile, Arizona researchers are exploring satellites and lunar orbits to host data storage, arguing that space deployments could eliminate water cooling needs and reduce environmental stress. Yet these ambitions face major obstacles: latency (especially for real-time services), reliability in harsh space environments, high launch and maintenance costs, radiation damage, and regulatory and engineering complexity.

Sources: IEEE Spectrum, Data Center Knowledge

Key Takeaways

– Moving data centers to space could dramatically reduce Earth-side burdens—electricity, cooling water, environmental impact—but the trade-offs in latency, cost, and reliability are steep.

– Some experiments are already underway (e.g. satellite concepts, lunar payloads) to test whether space-based infrastructure can be made resilient and cost-effective.

– For real-time, latency-sensitive applications (gaming, video streaming, live monitoring), space is likely not a viable replacement in the near term; more likely candidates are archival storage, non-critical AI training, or disaster recovery systems.

In-Depth

The notion of transplanting data centers into orbit or even onto the Moon might sound like science fiction, but it’s moving toward the frontier of engineering and corporate strategy. On Earth, data centers already strain local power grids, demand huge amounts of water for cooling, and contribute significantly to GHG emissions—especially AI-driven operations, which are projected to grow their power usage dramatically over the next few years. WIRED highlights that for many hyperscale operators, continuing to build more ground-based capacity means confronting rising energy costs, regulatory pushback, and environmental limits.

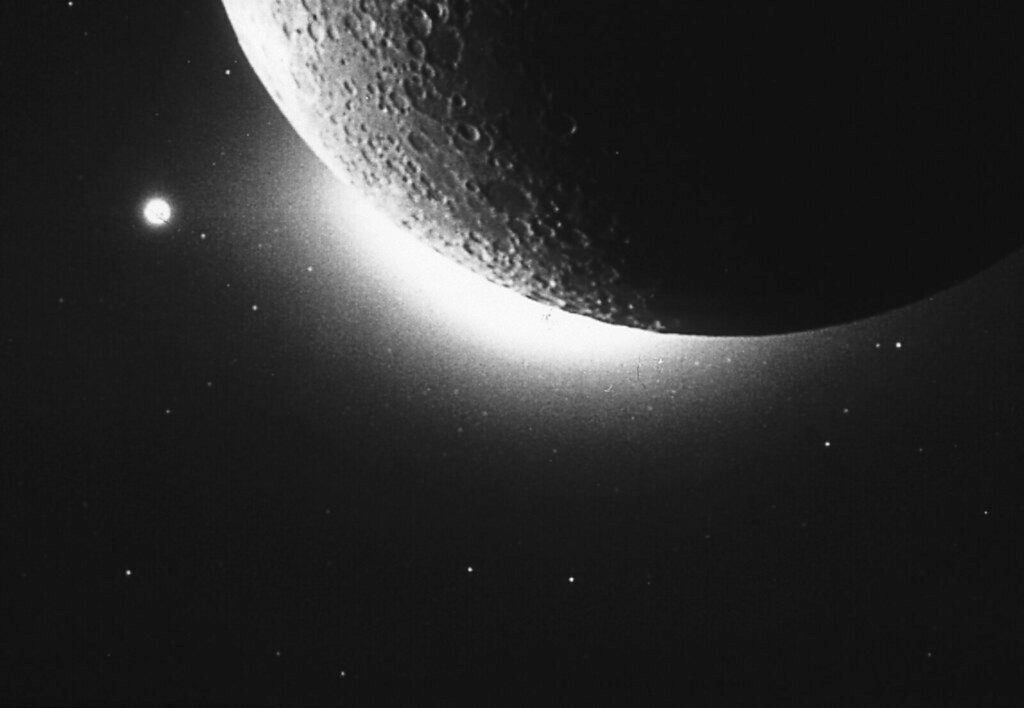

In response, several players are investigating whether space offers a cleaner, more sustainable alternative. In Arizona, university scientists have proposed using satellites or lunar orbits for data storage, citing the advantages of constant solar exposure (for power), minimal interference with local ecosystems, and the elimination of water cooling demands. There’s also lunar data-center proposals (like Lonestar’s “Freedom” project) that focus not on mission-critical latency but rather on backup, archival, and prevention of catastrophic data loss.

Yet turning these ambitious ideas into workable infrastructure is far from guaranteed. First, latency is a showstopper for anything needing near-instant response: placing servers on the Moon, for example, introduces about 1.4 seconds of one-way delay, ruling out applications like live video games, autonomous vehicle control, and high-frequency trading. Then there are issues of reliability—radiation damage, thermal extremes, cosmic micrometeoroids, the difficulty of maintenance and upgrades once deployed.

Cost is another major barrier: even with decreasing launch costs, putting massive computing infrastructure into space is vastly more expensive than building on Earth, unless breakthroughs in launch economics or space manufacturing occur. Regulatory and legal frameworks are also underdeveloped: who governs, insures, or regulates space‐based compute? How is data sovereignty maintained?

Still, there are glimmers of feasibility. Launch and satellite tech are improving; small experiments (e.g. small cubesats, prototypes) are testing components of space-data infrastructure. Also, not all data workloads demand low latency: AI training, big data archiving, backup, disaster recovery are more forgiving of delay. For these, space could serve as a valuable complement rather than a replacement.

In short: the push to move data centers off-planet is being treated less as fantasy and more as a long-term strategic bet. It won’t replace terrestrial infrastructure any time soon for most applications, but the environmental pressures—rising costs, diminishing resources, regulatory constraints—are making it a research priority. The question is not merely if it can be done, but when the economics and engineering will line up so it’s competitive—and which kinds of data workloads are shifted first.