In a rare and forceful maneuver, the Dutch government has assumed control over the Netherlands-based semiconductor company Nexperia, citing “serious governance shortcomings” that could threaten European technological sovereignty. The move was made under the seldom-used Goods Availability Act, allowing the state to block or reverse company decisions deemed harmful, though day-to-day operations may continue. The parent company, China’s Wingtech, slammed the intervention as “excessive interference” and signaled legal action, while its shares plunged 10 percent in Shanghai. This reflects mounting tensions in the global tech supply chain as Western powers reexamine Chinese stakes in strategic industries.

Key Takeaways

– The Dutch government invoked the Goods Availability Act—a Cold War–era emergency statute—due to concerns that Nexperia’s governance and connection to its Chinese parent risked leaking critical chip technologies abroad.

– Wingtech, the Chinese owner of Nexperia, denounced the move as geopolitically motivated and said it would seek legal remedies; its shares immediately dropped ~10 percent on the Shanghai exchange.

– This incident marks a sharper turn in Europe’s stance toward Chinese investment in high tech, signaling that governments may more readily intervene in “strategic sectors” under the banner of national economic security.

In-Depth

The Netherlands government took the semiconductor world by surprise when it intervened in Nexperia, a Dutch chipmaker controlled by China’s Wingtech, declaring the move “highly exceptional.” Utilizing the rarely deployed Goods Availability Act, the Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs asserted authority to review, block, or reverse key decisions within Nexperia—though it stipulated that regular production would continue. The government framed its actions as necessary to protect European interests, arguing that “serious governance shortcomings” within Nexperia threatened the preservation of crucial technological knowledge on Dutch and European soil.

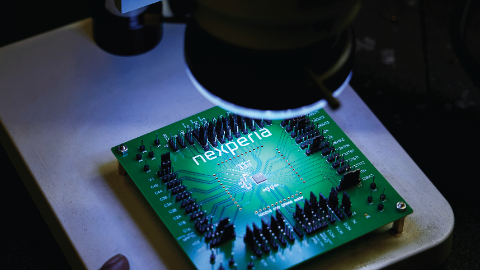

Nexperia, headquartered in Nijmegen and formerly part of Dutch electronics giant Philips/NXP, was acquired by Wingtech years ago. Because of its role in producing basic semiconductors—such as diodes, transistors, and other discrete components used widely across automotive and consumer electronics—its control is considered strategically sensitive. The Dutch government emphasized its interest in assuring that finished and semi-finished goods made by Nexperia remain reliably available in emergencies.

Wingtech immediately pushed back, calling the Dutch intervention “excessive interference driven by geopolitical bias” and announced intentions to challenge the decision legally. Meanwhile, its stock tumbled 10 percent in Shanghai trading following the news. The timing aligns with growing Western scrutiny of Chinese holdings in key tech infrastructure: only recently, the U.S. placed Wingtech on its Entity List to restrict its access to critical technologies, and the EU has been tightening investment screening regimes.

While not converting Nexperia into a full state-owned enterprise, the Dutch maneuver serves as a strong signal: in matters of technology sovereignty, European states may no longer tolerate distant or opaque oversight, even when the shareholder is a foreign entity. This incident may set a precedent for future interventions across Europe’s high-tech sector, highlighting how governments are increasingly willing to leverage legal instruments—even emergency ones—to guard against perceived threats to economic security.