Autolane, a Palo Alto startup, has raised $7.4 million to build what it calls “air-traffic control for autonomous vehicles,” a system designed to coordinate where and how self-driving cars pick up and drop off passengers or deliveries. The firm has already struck a deal with retail real estate giant Simon Property Group to deploy its technology at shopping centers in Austin and San Francisco, creating physical infrastructure — signs, curb-side markers — and backend software that guides autonomous vehicles precisely to designated curb zones. Backed by venture firms such as Draper Associates and Hyperplane, Autolane is positioning itself as a necessary middle-man: not building the cars themselves, but orchestrating their real-world movement on private properties as robotaxi deployment accelerates.

Sources: Futurism, WebPro News

Key Takeaways

– Autolane aims to solve the “last-50 feet” bottleneck for autonomous vehicles — the often-chaotic moment when robotaxis or delivery bots arrive at curbsides for pickups and drop-offs.

– Their business model targets private properties (shopping centers, retail lots, fast-food drive-thrus) rather than public streets; they work B2B, providing infrastructure and software to property owners and fleet operators.

– With no direct competitors yet, Autolane hopes to become the de-facto standard for curbside coordination as autonomous vehicle fleets scale.

In-Depth

As autonomous vehicles inch closer toward wider rollout — not just as futuristic prototypes, but as actual robotaxis and delivery agents on real streets — a less glamorous but far more urgent challenge is emerging: what happens when these vehicles arrive at a destination and need to pull up, stop, and deliver or pick up passengers or goods. Roads and curbsides were built for human drivers — not for fleets of computer-controlled vehicles navigating tight corners, narrow lanes, and unpredictable curbside chaos. Enter Autolane, a startup that recognizes exactly this practical bottleneck and has stepped in to build what its CEO calls “air traffic control for autonomous vehicles.”

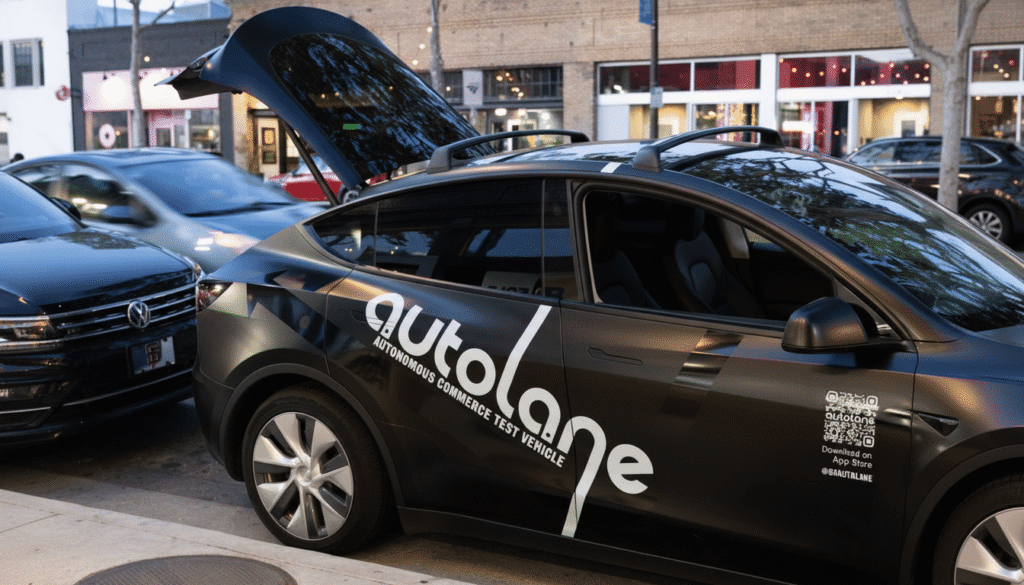

On December 3, 2025, Autolane announced it raised $7.4 million in funding — with backing from VC firms including Draper Associates and Hyperplane — and revealed a deal with Simon Property Group to roll out its curb-management system at shopping centers in Austin, Texas, and San Francisco, California. The plan: install a combination of physical infrastructure (curb-side signage, designated pickup/drop-off stanchions reminiscent of ride-hail zones at hotels or airports) and a software-driven backend. Autonomous-vehicle fleets would integrate with Autolane’s system so each vehicle is precisely guided to a designated “curb slot,” avoiding double parking, congestion, or confusion.

What’s striking about Autolane’s strategy is how conservative — and potentially realistic — it is. The company isn’t trying to build AI driving systems, sensors, or self-driving cars. Instead, it bets on being the middleman: a coordination layer between fleets and property owners. As CEO Ben Seidl told reporters, this isn’t about lofty visions of smart cities or fully optimized urban design. It’s about short-term, concrete problems: how to get a robotaxi to a correct spot at a mall or fast food joint so a rider can get in or a delivery can be dropped off — and then get out again without clogging the curb.

That humility may give Autolane a real shot at being indispensable if robotaxis and delivery fleets scale as many expect. Right now, no company appears to be tackling this problem at scale in a generic, fleet-agnostic way, giving Autolane an opening. As autonomous vehicles proliferate across cities, everything from ride-hailing to grocery deliveries might rely on precisely this kind of coordination at the “last 50 feet.” Because once a self-driving car drops you off or picks up your food, all that really matters is how smoothly it arrives and departs — and that’s where Autolane is carving out its niche.

Of course, there are downsides and trade-offs baked into Autolane’s approach. First, by focusing exclusively on private properties — malls, retail centers, drive-thrus — the company sidesteps the messier world of curb management on public streets, where regulations, public-space politics, and municipal bureaucracy are harder to navigate. That means the benefits may stay limited to controlled environments — not necessarily helping with everyday congestion in dense urban neighborhoods. And second, this model doesn’t challenge the underlying car-centric design of suburbs, malls, and strip-retail zones; it treats the existing layout as fixed and tries to navigate around it, rather than rethinking it.

In that sense, Autolane’s solution is very much a product of the current urban reality — one tuned not for high-minded urban planning or pedestrian-friendly streets, but for a near future where robotaxis blend into the existing car-centered infrastructure. If autonomous fleets do take off, and retail outlets, drive-thrus, and malls begin to accommodate them, Autolane could become a quiet enabler of a major shift in how we commute, shop, and get deliveries. But it also underscores that the broader promise of self-driving technology — smarter cities, less traffic, fewer parking lots — may get delayed or diluted. Instead of reshaping urban design, we may just be layering more high-tech coordination on top of infrastructure built for a bygone era of gas-powered cars.