Researchers have developed a method that decodes brain activity tied to viewing or recalling video content and transforms it into coherent textual descriptions — all without relying on the brain’s traditional language-centres. According to the report on Neuroscience News, the system termed “mind captioning” uses fMRI scans to capture visual and associative brain responses, then applies deep-learning models to generate structured sentences that preserve relational meaning (for example, distinguishing “a dog chasing a ball” from “a ball chasing a dog”). A separate article from Nature frames the advance as a non-invasive technique that could translate scenes in a person’s mind into sentences — pointing both to major potential and serious ethical questions. Meanwhile, broader work in brain-computer interfaces shows parallel advances in decoding inner speech and non-verbal neural activity, underscoring how the boundary between thought and machine-read text is rapidly narrowing.

Sources: Neuroscience News, Nature

Key Takeaways

– The new “mind captioning” method decodes semantic brain activity triggered by visual stimuli (or memory of them) into readable text, bypassing typical speech-oriented brain regions.

– Generated descriptions capture not just isolated objects but relational meaning (actions, context, relationships) — a major step beyond earlier keyword-based brain decoding.

– Although promising for assistive technologies (e.g., for non-verbal patients), the technique raises privacy and ethical concerns because thoughts may one day be translated without speaking.

In-Depth

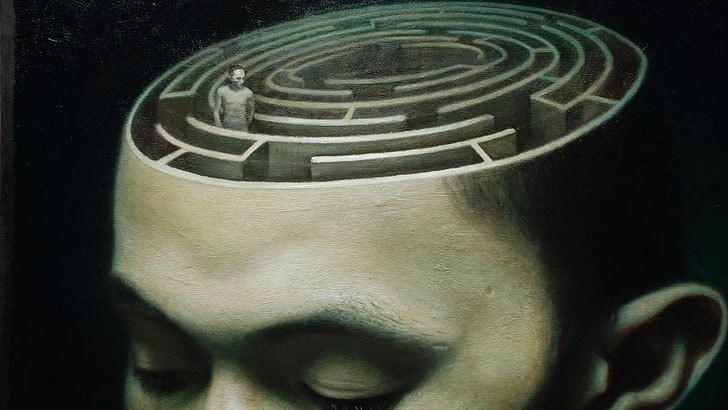

In a world increasingly shaped by the blending of neuroscience and artificial intelligence, a recent advance stands out: the development of a system that can translate what you’re seeing—or remembering—directly into text. This isn’t about decoding words you think in your head; it’s about decoding the semantic structure of what your brain perceives or recalls. Researchers used functional MRI to record brain-wide activity while participants viewed video content or later recalled it from memory. Instead of focusing on language areas of the brain, the system looked at the brain’s visual and associative networks and trained deep learning models to map those patterns into semantic representations. From there, the model generated coherent sentences. That process alone is remarkable: the system didn’t just identify “dog,” “ball,” “chase,” it understood “a dog chasing a ball,” preserving the directionality and relationship of action. According to the Neuroscience News report, shuffling the word order in the generated sentence significantly degraded the system’s ability to match brain activity — meaning the structure matters, not just the words.

What sets this apart from earlier brain-computer interface (BCI) work is the bypassing of the conventional language centres. Even when the language-regions were excluded from analysis, the system still succeeded at generating meaningful text. This suggests that our brains encode high-level semantic information (objects, actions, relationships, context) in networks outside the traditional language hubs. The Nature article describes this as a “mind-captioning” technique that generates sentences from non-invasive imaging of brain activity.

What does this mean in practical terms? For individuals who are unable to speak or write—those with locked-in syndrome, paralysis, severe aphasia—the possibility of communicating by thought alone becomes less far-fetched. A user could imagine or recall an experience, and a machine might translate that into text which could then be spoken or displayed. The implications for assistive tech are huge. However, the technology is still in its early stages and comes with caveats: it currently requires intensive calibration per individual and uses expensive, non-portable fMRI equipment. The ethical terrain is also fraught. If thoughts—or the sense of what one saw and remembers—can be converted into text, issues of mental privacy, unintended mind reading, or misuse of decoded brain content become real concerns.

From a broader vantage, this fits into a trajectory of neural decoding becoming more sophisticated. Previous work has focused on decoding inner speech or attempted speech from motor-cortex implants with decent accuracy (for example up to ~74% in some cases).

But decoding pure visual or mental imagery into language is a different frontier. For your work in media production and content creation, this kind of tech suggests an emerging future where cognitive content (memory, vision, imagination) might be captured or translated in new ways. For example, imagine capturing a subject’s mental imagery and turning it into a written narrative or a storyboard automatically. It raises interesting possibilities for storytelling, podcasting, documentary work, but also serious responsibility in how any such tool is used.

For conservative audiences, a few reflections: first, the capacity to decode thought challenges long-standing notions of personal mental privacy and autonomy. The idea that inner experiences are wholly private may need to be re-examined. Second, while the assistive applications are compelling and moral, the pace of technological advancement means regulatory and ethical frameworks must keep up — ideally grounded in respect for individual rights, transparent consent, and due consideration of misuse (surveillance, coercive applications). Finally, there’s a human-centric argument: technologies that enable voice and agency for the disabled are undeniably good, but we must retain focus on human dignity, meaningful choice, and the centrality of human-to-human communication rather than complete machine substitution.

In summary: decoding brain activity into language is no longer just the stuff of science fiction. While the current demonstrations are lab-bound and calibrated, the trajectory is real. For creators like yourself working at the intersection of media, technology, and human narrative, keeping an eye on how these tools evolve — and how they might complement storytelling or assistive communication — will be a smart strategic move. At the same time, championing frameworks that protect privacy, consent, and human value will remain as important as the technology itself.