A SpaceX Starlink satellite narrowly avoided a catastrophic collision last week when a Chinese-launched spacecraft came within roughly 200 meters during an uncoordinated pass in low Earth orbit, highlighting serious safety concerns as orbital traffic surges and international coordination remains limited.

Sources: Space, Tom’s Hardware

Key Takeaways

• The incident involved Starlink-6079 and a Chinese payload deployed from a Kinetica 1 rocket without shared trajectory data, underscoring risks from uncoordinated satellite operations.

• SpaceX engineering leadership publicly criticized the lack of data sharing, calling for improved space traffic management standards to prevent future near-misses or worse.

• With thousands of satellites now in low Earth orbit, the risk of debris and collision cascades — often referred to as Kessler syndrome — grows as commercial and national operators accelerate deployments.

In-Depth

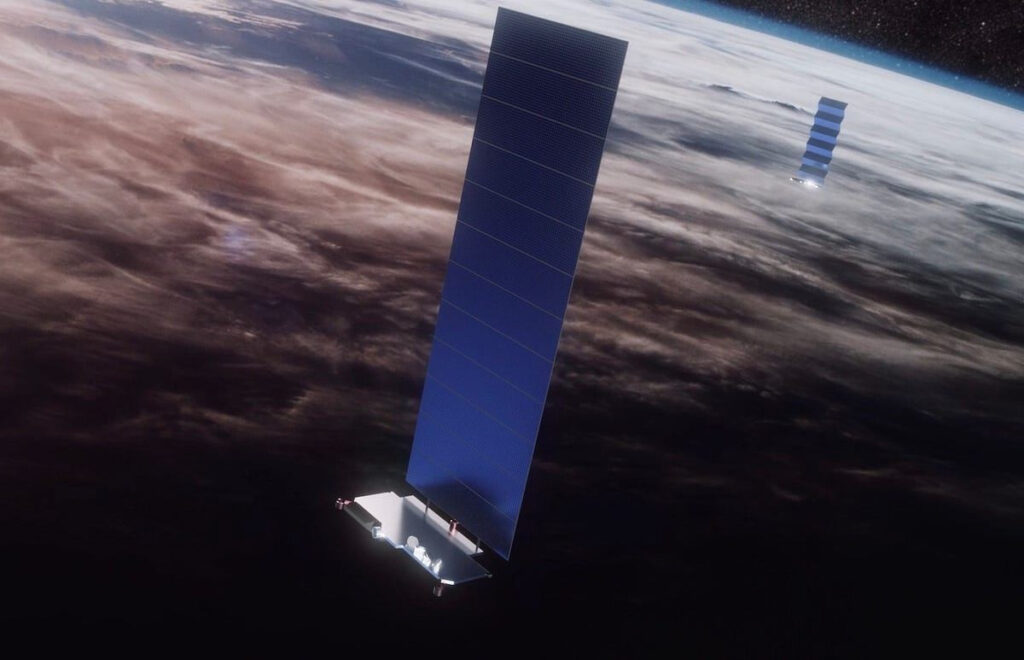

Last week’s near collision between a Starlink internet satellite and a Chinese spacecraft serves as a stark reminder that low Earth orbit is fast becoming a dangerously crowded environment, with inadequate international coordination heightening the risk of disaster. On December 9, a Chinese Kinetica 1 rocket launched multiple satellites, one of which passed within approximately 200 meters of SpaceX’s Starlink-6079 at about 560 kilometers above Earth. Because the Chinese operator did not provide ephemeris or trajectory data to other orbital traffic tracking systems before or after launch, Starlink’s collision-avoidance systems did not have advance knowledge of the object’s path. Starlink engineering vice president Michael Nicolls publicly warned that the absence of shared orbital data — which would allow satellite constellations to avoid one another safely — substantially increases the risk of catastrophic collisions and a growing debris field.

At speeds exceeding 17,000 mph, even small miscalculations in orbit can produce debris fields that imperil other satellites, including critical communications and scientific infrastructure. As global mega-constellation deployments ramp up on both commercial and national fronts, the sheer number of active satellites is projected to climb sharply. This expansion places added strain on already limited frameworks for space traffic management and highlights the urgent need for binding international standards on data sharing and collision avoidance.

China’s space company, CAS Space, responded by saying that its launches consider space awareness systems and that the close approach occurred after its mission concluded, but it also acknowledged the broader importance of coordination. Meanwhile, space safety advocates point out that without enforceable protocols and real-time data exchange among operators worldwide, the growing population of objects in low Earth orbit could lead to the very scenario that engineers fear most: a cascade of collisions that could render vital orbital pathways unusable for years to come. In the context of accelerating competition for satellite internet dominance and national prestige, this incident accentuates the need for pragmatic policy solutions that protect shared orbital space without stifling innovation.