In a recent review, researchers outline how injectable hydrogels are emerging as a promising scaffold and drug-delivery system for repairing nervous tissue after injury—particularly given that standard treatments remain invasive and often ineffective. The article highlights that these hydrogels can be administered minimally invasively, conform to injured tissue micro-environments, support cell survival and regrowth, and deliver bio-active factors. Additional reviews reinforce that functionalized and injectable hydrogel systems are gaining traction for both central and peripheral nervous system repair.

Key Takeaways

– Injectable hydrogels offer structural and biochemical support suited to nervous-tissue micro-environments, enabling less invasive delivery compared to conventional scaffolds.

– Many current hydrogel systems incorporate bio-active cues (growth factors, peptides, stem cells) and are engineered with tunable mechanical/biodegradation properties to match nervous tissue requirements.

– Despite promising pre-clinical data, significant translational hurdles remain—including long-term safety, functional integration in vivo, and scaling from lab to clinical therapies.

In-Depth

The field of nervous-tissue repair is steadily shifting toward biomaterials capable of being injected, deployed in situ, and tailored for the delicate architecture of the nervous system. A noteworthy example of this trend is the 2024 review by Politrón-Zepeda and colleagues (“Injectable Hydrogels for Nervous Tissue Repair – A Brief Review”), which consolidates in vitro and in vivo work showing how injectable hydrogels hold clear promise for neural-regenerative medicine.

Traditional approaches to nervous-system injury—whether traumatic brain/spinal-cord injury or peripheral-nerve lesion—have been hampered by both biological and mechanical limitations: the nervous system has limited intrinsic regenerative capacity; scar tissue interferes with regrowth; and surgical implants or conduits often fail to replicate the native extracellular matrix (ECM) environment. The review points out that conventional scaffolds are often invasive to implant and may not adapt well to complex lesion geometries. Injectable hydrogels, on the other hand, can be delivered through a syringe, conform to irregular injury sites, and gel in situ, thereby reducing implantation trauma and improving scaffold-lesion contact.

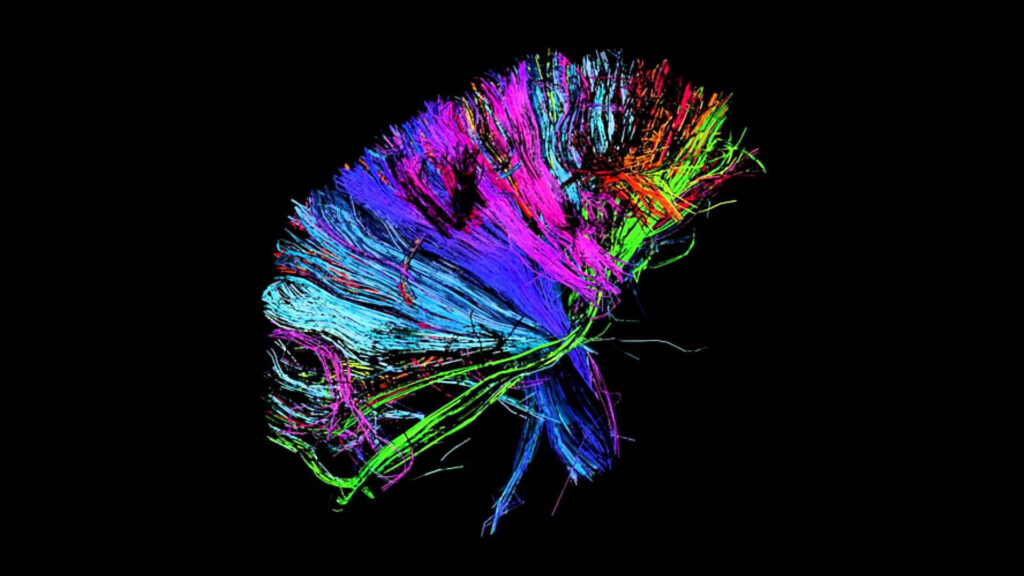

From a materials science standpoint, these injectable hydrogels are engineered to mimic several key traits of nervous-tissue ECM: high water content, a porous 3D structure, mechanical compliance similar to soft neural tissue, and the ability to embed or release therapeutic agents (growth factors, stem cells, small molecules). Politrón-Zepeda et al. review how newer hydrogel constructs incorporate chitosan/β-GP, hyaluronic acid–RADA peptide systems, self-healing networks, and other sophisticated cross-linked frameworks that permit cell infiltration, axonal guidance, and biocompatible degradation.

Complementing this work, Zhao et al. (2023) provide a review of functionalized hydrogels for neural injury repair, emphasizing recent strategies in which hydrogels are endowed with dopaminergic-mimetic functionality, conductive elements, or neurogenic growth-factor binding domains to promote neuron survival and synapse formation. Their key message: delivering neural cells or growth factors is only half the battle—the supportive microenvironment plays a critical role, and injectable hydrogels are well-positioned to provide it.

What does this mean for the future of treatments for nerve injuries and neurodegenerative disease? From a conservative perspective, the potential is real—but so are the risks and impediments. On the positive side, injectable hydrogels offer a minimally invasive delivery route, reduce foreign body mass compared to rigid implants, and can be fine-tuned in terms of mechanical and biochemical cues to reflect patient-specific lesions. They may allow earlier intervention after injury, improve cell survival, reduce scar formation, and ultimately better functional recovery (motor, sensory, cognitive). On the cautionary side, the translation from animal models to human therapy remains murky. It is one thing to show axonal regrowth or cell survival in a rat sciatic-nerve injury; it is quite another to restore meaningful human motor/sensory function in a complex spinal cord injury, or to demonstrate durability and safety over many years. Key concerns include immune/inflammatory reactions, hydrogel degradation products, integration with host tissue, and consistency in manufacturing and regulatory approval pathways.

From a regulatory and economic standpoint, injectable hydrogels will likely face scrutiny over cost, scalability, and long-term outcomes. Conservative fiscal stewardship requires that new therapies demonstrate compelling benefit over existing standards of care (nerve grafts, conduits, surgical repair) and show durable improvement in patient function. Without such evidence, the adoption may remain limited to niche or adjunctive use. For patients and clinicians, the message is: this is a promising adjunct to the toolkit—not yet a proven primary therapy. But as materials science continues to mature, and as pre-clinical successes accumulate, injectable hydrogels could become an important option for surgeons, neurologists and rehabilitation specialists.

In short, the emergence of injectable hydrogels for neural-tissue repair reflects a broader shift in biomedical engineering—from one-size-fits-all implants toward bio-active, patient-tailored materials that adapt in situ. For the conservative investor in health-tech or the prudent clinician evaluating emerging therapies, the key will be to watch for large-scale trials demonstrating both safety and functional outcomes. If and when that arrives, injectable hydrogels may move from pre-clinical promise to standard practice—offering new hope for patients with nerve injuries that today are difficult to treat.