Researchers are making strides in growing human brain tissue in the lab that can interpret electrical signals akin to a computer, with the aim of ultimately creating supercomputers that use far less energy than conventional silicon-based machines. One recent overview reports that university labs and startups are cultivating small “brain blobs” (about the size of a grain of sand) composed of human neurons and glial cells, then interfacing them with electrodes so that they can receive tasks, respond electrically, and potentially perform computing functions. According to “Semafor,” these efforts could lead to reliable, energy-efficient supercomputers built with biological substrates. Additional reporting from Nature and National Geographic confirms that this field—called “wetware” or “organoid intelligence”—is gaining momentum, as scientists explore how the human brain’s extraordinary energy-efficiency might be harnessed in computing.

Sources: Nature, National Geographic

Key Takeaways

– Labs are successfully cultivating human-derived brain tissue (organoids) that can process electrical signals and interact with external inputs, moving beyond mere biological models into computing-capable substrates.

– The major appeal is energy efficiency: the human brain uses only ~20 watts to perform massive parallel tasks, far less than large silicon supercomputers, making biological computing a potentially transformative path for low-power high-performance systems.

– Despite the promise, significant hurdles remain—scaling up tissue size and stability, integrating biological and electronic interfaces reliably, ethical questions about consciousness or sentience, and the need for nutrient/support infrastructure for living computing matter.

In-Depth

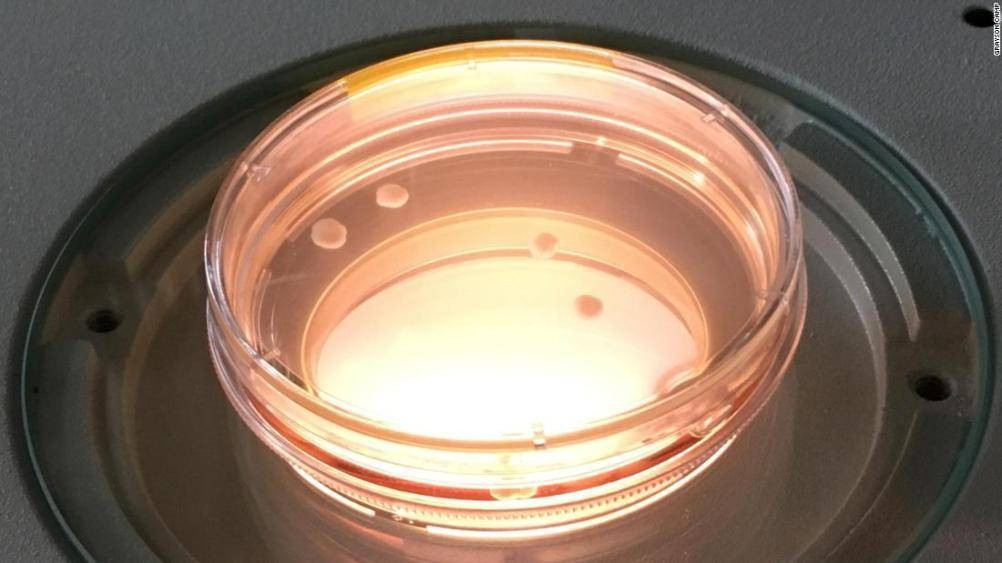

In the world of computing, engineers and researchers have long been constrained by the limits of silicon-based technologies: heat dissipation, energy consumption, and ever-shrinking transistor sizes. Meanwhile, the human brain quietly operates at roughly 20 watts yet achieves parallelism and efficiency that far outpaces conventional processors. Recognizing this, scientists are now turning to an extraordinary frontier: growing human brain tissue—organoids—in the lab, and using them as living computational substrates. As reported by Semafor, Nature, and National Geographic, small clumps of cultured human neural tissue have been coaxed to receive electrical stimuli, respond via multi-electrode arrays, and even perform tasks reminiscent of basic computing. These experiments remain nascent, but the vision is bold: supercomputers that work not with millions of transistors, but with thousands of living neurons, consuming orders of magnitude less energy.

At the heart of this effort is the concept of “organoid intelligence” or “wetware computing.” Unlike artificial neural networks running on electronic hardware, which simulate brain-like activity but still rely on energy-hungry silicon, organoid systems attempt to harness real biology. A Nature article described “grain-of-sand” sized clusters of human neurons that labs can remotely load tasks into and read responses back from. Meanwhile, National Geographic noted that researchers are experimenting with cultured brain cells integrated into micro-electrode arrays and chips in bid to replicate neural processing in a computer-relevant fashion. The driving promise: if one can harness the human brain’s efficiency for computation, it could revolutionize supercomputing, data centers and AI infrastructure by dramatically cutting energy use, thereby aligning with conservative goals of technological efficiency, economic prudence and reduced resource consumption.

Nevertheless, the road ahead is rugged. Living tissue must be kept viable — supplied with nutrients, oxygen, and protected from degeneration. Interfacing living neurons with silicon electronics raises reliability and longevity questions: can biological tissue function continuously, scale to useful sizes, and maintain consistent behavior? And crucially, there are ethical and regulatory implications: if one uses human-derived neural tissue, at what point does it become conscious or entitled to protections? Some experts caution that we’re far from creating sentient machines, yet responsible development must guard against unintended consequences.

Moreover, from a practical standpoint, translating lab-scale experiments into large-scale computing infrastructure would require massive shifts in how data centers are built and maintained. Traditional rack-based server farms may need to incorporate bioreactors, chillers, nutrient circulators and living neuron arrays rather than purely solid-state electronics. For conservative tech strategists, this presents both an opportunity to leapfrog energy-intensive computing models and a caution: the transition will involve technological risk, infrastructure complexity and regulatory uncertainty.

Still, the potential upside is compelling. Imagine supercomputers running on biological substrates with orders of magnitude less energy, enabling advanced AI, modeling and data processing without the carbon- and cost-intensive stacks of today. For organizations keen on cost control, energy savings and long-term scalability, investing in or monitoring developments in this domain could yield strategic advantages. At the same time, policy makers and ethics boards should begin working in parallel to craft frameworks for responsible use of human-derived computing tissues. In the convergence of neuroscience and computer engineering lies a paradigm shift that could favor those who combine technological foresight with conservative discipline: minimizing waste, maximizing efficiency, and deploying next-generation systems that align with sustainable principles rather than endless consumption.

In short: we may still be years away from data centers powered by living human neural tissue, but the early breakthroughs suggest a credible path forward. For any organization or individual scanning the horizon of computing innovation—from retirement-plan tech firms to digital-media platforms—the implications are worth watching. The brain’s efficiency is no longer just a marvel of nature: it may become the blueprint for tomorrow’s supercomputers.