South Korea has long enforced a statutory workweek cap of 52 hours—40 standard hours plus up to 12 hours overtime—to rein in overwork and boost worker welfare. According to recent reporting, however, the country’s fast-moving tech and deep-science sectors are feeling squeezed by this constraint as they compete globally and watch the “996” culture (9 am to 9 pm, six days a week) take root in neighbouring China. One venture-capital CEO in Korea flagged the rule as a notable barrier to investment in AI, semiconductor and quantum-computing firms. At the same time, the Korean government has introduced limited exemptions—such as a temporary increase of the cap to 64 hours in specified sectors under labour-management agreement—and lawmakers are pushing to loosen the cap further, particularly for chip manufacturers. The dynamic suggests a tug-of-war between productivity-driven competitive urgency and longstanding labor protections.

Sources: Korea Herald, ChoSun.com

Key Takeaways

– The 52-hour workweek cap in South Korea—originally introduced to moderate excessive hours—is increasingly viewed by tech investors and startup founders as a hindrance to rapid innovation in globally competitive sectors.

– The spillover of China’s “996” ultra-work culture puts added pressure on Korean firms to keep pace, prompting calls for greater flexibility or exemptions in labor rules for R&D-intensive industries.

– The government is caught between two objectives: maintaining worker protections and promoting an environment that supports high-tech growth; the recent move to permit temporary longer hours in certain sectors signals a shift toward privileging competitiveness over rigid hour limits.

In-Depth

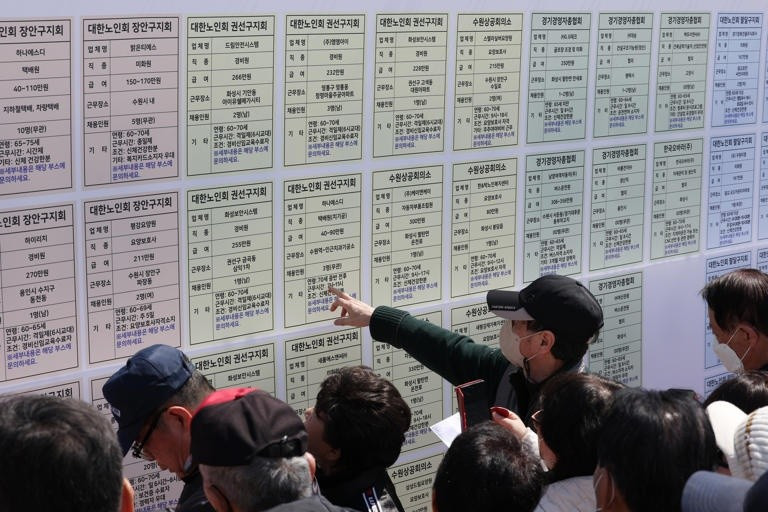

South Korea’s labour regulation environment is undergoing tension and recalibration as the country’s tech and deep-science sectors strive for global competitiveness. For years, Korea has mandated a maximum workweek of 52 hours—40 regular hours plus up to 12 hours of overtime—applicable across most businesses. The rule, phased in beginning 2018, was part of an effort to reduce Korea’s high work-hour culture and improve quality of life for employees. Data show that overtime hours and extreme workweeks have declined under the cap: as of 2022, about 12 % of Korean workers logged more than 50 hours per week, down dramatically from previous decades. According to one study, the share of workers clocking over 60 hours has been cut by roughly six-sevenths since the cap’s introduction.

However, in the fiercely competitive domain of tech — especially in areas like semiconductors, artificial intelligence, quantum computing and other deep-tech ventures — many feel that 52 hours is too restrictive. A venture capital executive pointed out that early-stage companies often need periods of intense focus and long hours to hit critical development milestones, and the legal hour cap limits that flexibility. At the same time, Korea’s neighbour China has become more tolerant (or at least less visibly constrained) by ultra-long-hour regimes, notably the so-called “996” schedule (9 am to 9 pm, six days a week, i.e., 72 hours) which is widely used in Chinese tech firms despite being formally illegal. The cultural diffusion of “996” norms—emphasising long work, sacrifice and relentless pace—adds pressure on Korean firms to adapt if they are to compete globally.

Recognising this pressure, the Korean government has been exploring more flexible arrangements in key strategic industries. In the semiconductor sector, for example, Korea temporarily extended a special overtime exemption from three months to six months, allowing certain firms to exceed the 52-hour weekly cap if worker agreement and government approval are in place. Some lawmakers are actively pushing for legislation to exempt chip-fabs and R&D from the 52-hour rule entirely or raise the cap for those segments. They argue that rivals like Japan and Taiwan already permit longer workweeks and that Korea risks falling behind. Opponents, including labour unions and worker-rights advocates, warn that relaxing limits undermines decades of progress toward better work-life balance and risks reigniting overwork problems.

From a conservative vantage point—emphasising free-market growth and global competitiveness—the argument is strong: if Korean firms cannot match the intensity and tempo of rivals abroad, they may cede leadership in critical fields, lose investment and drop out of strategic value-chains. The 52-hour cap, while socially commendable, may end up constraining growth in sectors where ‘time to market’ and product-cycle speed matter. On the other hand, sacrificing worker welfare and encouraging excessive hours risks human capital burnout and reputational damage. The optimal path likely involves a calibrated balance—preserving the cap for most industries to maintain social stability, while carving out targeted, well-monitored exemptions or alternative frameworks for high-strategic sectors.

In practice, the coming months could see legislative proposals, pilot programmes and negotiations among government, business and labour stakeholders to define which industries qualify for greater flexibility, under what conditions, and with what safeguards for workers. For investors and international firms watching Korea as a tech-ecosystem hotspot, how this tension resolves will be a key variable in assessing Korea’s attractiveness: a system too rigid may dissuade rapid-moving startups; a system too lax may expose companies and employees to long-term risks. The outcome could influence where global capital flows, which countries dominate the next wave of chip and AI innovation, and whether Korea remains a leader or becomes a follower.

In short, South Korea’s 52-hour week is a social achievement—but in a world where speed, long hours and global race logic dominate tech, it may need revision. The balance between worker protection and competitive edge is delicate, and how the country manages it could set an important precedent for other advanced economies grappling with similar trade-offs.