An internal document from SpaceX, obtained by media outlets, indicates that the firm’s giant Starship lunar-lander may not be ready to support NASA’s Artemis III moon-landing mission until September 2028 at the earliest, more than a year beyond NASA’s target of mid-2027. This delay comes amid mounting pressure on NASA, which has publicly stated that it will open the contract to other providers because of SpaceX’s slipping schedule. At the same time, SpaceX is reportedly simplifying its lander architecture and reducing the number of orbital refueling missions, but the pace and scale of the challenges remain significant. The confluence of contract uncertainty, technical risk and scheduling pressure raises the prospect of either a delayed lunar return, a re-bid of the lander contract or even a shift in which company carries U.S. astronauts back to the Moon.

Key Takeaways

– SpaceX’s timeline for its Starship-based lunar lander is slipping significantly, now pointing toward 2028 rather than a mid-2027 moon landing.

– NASA is responding by reopening the lander contract for its Artemis III mission, signalling doubt about SpaceX’s ability to meet its target.

– Technical simplifications by SpaceX (e.g., fewer tanker flights, streamlined architecture) may help—but they don’t erase the broader schedule risk or strategic implications of a missed landing deadline.

In-Depth

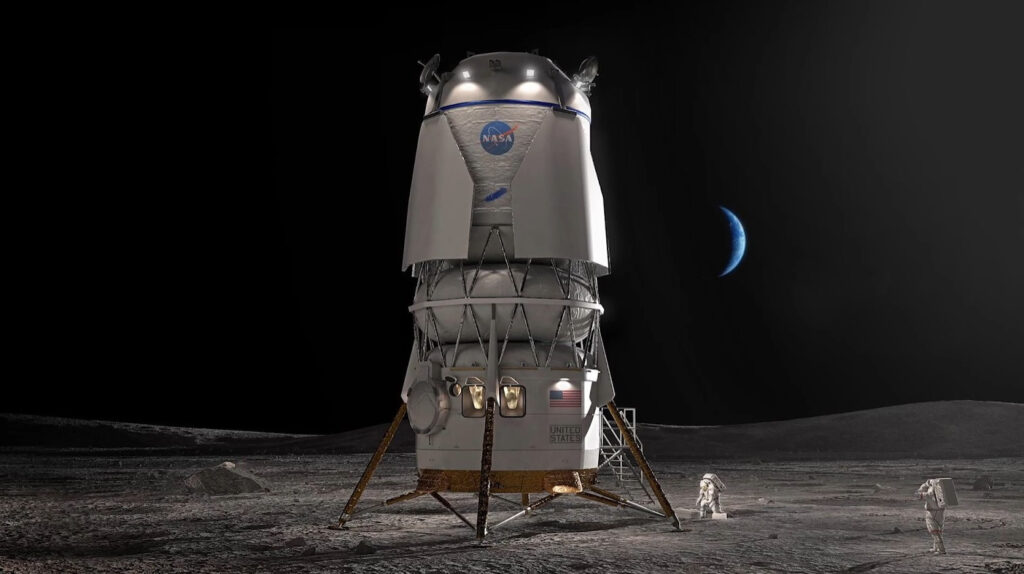

For years, NASA’s Artemis programme cultivated the image of a triumphant American return to the lunar surface: after decades of dormancy, U.S. astronauts would touch down on the Moon’s south pole, re-asserting American leadership in space. At the heart of that plan was SpaceX, under contract to deliver its Starship-based Human Landing System (HLS) to carry the crew of Artemis III to the surface. Originally aimed for mid-2027, the landing date is now in serious jeopardy.

SpaceX’s recently leaked internal schedule reveals a sobering reality: the firm anticipates achieving an uncrewed lunar landing no earlier than June 2027, and only a crewed lunar landing at the earliest in September 2028. That stands in direct tension with NASA’s target. What’s more, NASA’s leadership is openly admitting the risk. Acting Administrator Sean Duffy has stated that the agency is prepared to bring in other bidders for the lander contract—effectively signalling that the U.S. government views SpaceX’s delay as more than just routine slippage.

On the technical side, Starship’s complexity has proven formidable. A human-rated lunar lander must deliver massive propellant loads, support crew transfers, enable safe ascent and meet rigorous reliability standards. The architecture built by SpaceX envisioned perhaps a dozen or more orbital tanker flights to refuel the lander prior to descent; recent reports suggest SpaceX is now attempting to reduce that number by modifying the lander design and simplifying mission parameters. While that may be a prudent response to the risk of delay, it nonetheless reflects a step back from earlier, more aggressive plans.

The implications are broad. If Artemis III is delayed beyond 2027, the ripple effects could include longer gaps between lunar missions, a higher cost per landing, and increased international risk—most notably competition from China, which has publicly set sights on the Moon by 2030. Domestically, it raises questions about the procurement process and whether NASA’s heavy reliance on one contractor (SpaceX) left it vulnerable to schedule breakdowns. The decision to open the contract to others such as Blue Origin or Lockheed Martin underscores that concern.

From a conservative viewpoint, it’s worth noting that space exploration is expensive, high risk and often subject to optimism bias. Delays of this sort should not surprise anyone who is familiar with complex aerospace procurement; indeed, the Apollo programme encountered similar schedule and budget challenges during its early years. What is more worrisome is the degree to which national prestige and strategic leadership in space are tied to a single contract and supplier. If SpaceX falters, the consequence is less about embarrassment and more about a loss of operational momentum and leverage, possibly giving competitors or adversaries a window to advance while the U.S. stalls.

In the context of fiscal discipline, the government must ask whether the Artemis vision—frequent lunar landings, sustained presence, eventual Mars groundwork—is being pursued at the right tempo and cost structure. For taxpayers and policymakers alike, a re-bid or schedule slip is a moment to recalibrate expectations, demand accountability and reaffirm that leadership in space requires redundancy and realistic timelines.

Bottom line: just because the goal remains ambitious doesn’t mean the delivery schedule is realistic. NASA and SpaceX now face a joint test: either reset expectations and manage a new timeline, or risk ceding leadership in the next great era of lunar exploration.