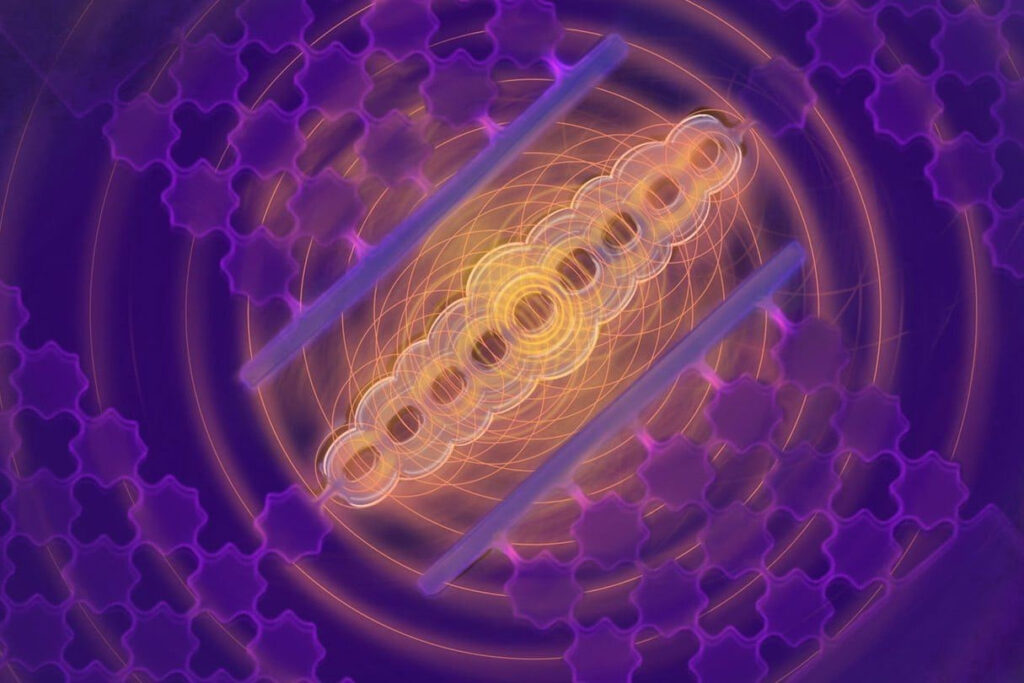

Caltech researchers, led by graduate students Alkim Bozkurt and Omid Golami under the supervision of Mohammad Mirhosseini, have developed an innovative hybrid quantum memory system that uses sound—in the form of mechanical oscillations or phonons—to store quantum information. By converting electrical signals from superconducting qubits into acoustic vibrations using a microscopic “tuning-fork” style mechanical oscillator, they’ve managed to extend the lifetime of quantum states by about 30 times compared to traditional superconducting systems. This approach promises more compact, scalable, and energy-efficient quantum memory, because acoustic waves don’t radiate energy into open space the way electromagnetic waves do, mitigating losses and crosstalk between devices. More broadly, this phonon-based storage method could play a significant role in advancing practical, reliable quantum computing.

Sources: Technology News, Innovation News Network, Quantum Computing Report

Key Takeaways

– Caltech has demonstrated a phonon-based quantum memory that extends qubit coherence times by roughly 30× compared to superconducting memory alone.

– The technique hinges on converting electrical quantum states into mechanical vibrations via a chip-integrated “tuning-fork” oscillator, offering compactness and reduced energy leakage.

– This development sits at the crossroads of quantum information science and electrical engineering, pointing toward more scalable and reliable quantum computing hardware.

In-Depth

Caltech’s latest breakthrough might just be the sort of practical advance quantum computing needs to move beyond lab proof-of-concepts and into scalable systems. By cleverly swapping fragile electrical quantum states for striker-like mechanical oscillations—think of a microscopic tuning fork vibrating at gigahertz frequencies—scientists have found a way to preserve quantum information up to thirty times longer than what’s possible with superconducting qubits alone. That’s huge. Quantum bits, or qubits, notoriously lose coherence fast, making long-term storage a real headache and a notable roadblock to reliable quantum machines.

Here’s why sound helps: acoustic waves, unlike electromagnetic signals, don’t escape into free space. That means less energy loss, less crosstalk, and a more compact footprint—critical for systems that need tight control and integration. Plus, these are devices that already play nicely with the ultra-cold, microwave-based superconducting circuits used in many labs today.

What I appreciate most is how this bridges quantum information science and electrical engineering in a smart, efficient way—no new exotic materials, no wild multi-step optical tricks, just good engineering wrapped around solid quantum physics. If the field can keep building like this—incrementally, steadily, with a clear path to real-world deployment—we might see functional quantum memories sooner than folks expect. It’s exactly the measured, dependable progress that policymakers and funders often look for: pushing frontier science while laying down the infrastructure for practical applications.