A recent cross-sectional study published in BMC Psychiatry involving 424 older adults (aged 60+) reveals a strong association between repetitive negative thinking (RNT) — characterized by frequent rumination or worry — and reduced cognitive performance. Using tools like the Perseverative Thinking Questionnaire (for measuring RNT) and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) for cognition, researchers found that individuals scoring in higher quartiles for RNT performed worse on overall cognition, memory, attention, and visuospatial tasks, even after adjusting for age, education, chronic illness, and other confounders. Complementing this, earlier studies show RNT also correlates with subjective cognitive decline among older adults and with biomarkers linked to Alzheimer’s disease such as amyloid and tau accumulation. These findings suggest RNT is more than a symptom of anxiety or depression—it may itself be a modifiable risk factor for cognitive impairment.

Sources: BMC Psychiatry, BioMed Central, Frontiers in Aging

Key Takeaways

– Repetitive negative thinking (RNT) in older adults is significantly associated with lower scores in objective measures of cognitive function (global cognition, memory, visuospatial ability), even after accounting for age, education, illness, etc.

– RNT is also related to subjective cognitive complaints and appears linked with established Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers (amyloid, tau), suggesting it may contribute to neurodegenerative processes, not just psychological distress.

– Because RNT is a psychological process rather than an immutable biological factor, there is real promise for interventions (e.g. cognitive behavioral therapy, mindfulness, cognitive training) to reduce RNT levels and possibly slow cognitive decline.

In-Depth

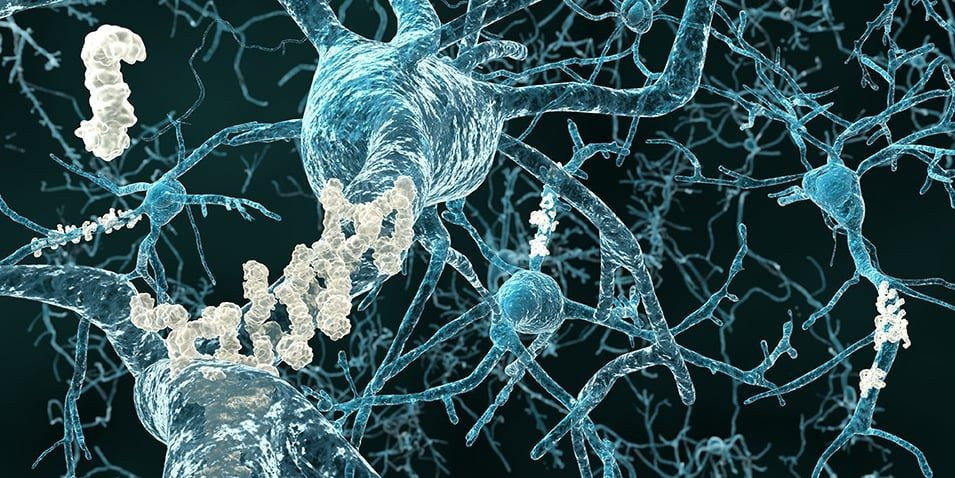

As we age, our bodies change in many visible ways — greying hair, slower walking, creaky joints. But the silent shifts inside the mind often go unnoticed until they become serious. Recent research adds to concerns that repetitive negative thinking — that loop of rumination about past regrets or worry about what’s ahead — does more than just make us feel anxious or down; it may be accelerating the loss of cognitive abilities in older adults. A study of 424 seniors in China aged 60 and above found that those who scored higher on a measure of such repetitive negative thinking (RNT) also scored worse on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), a test that covers memory, attention, visuospatial skills, verbal fluency, and general cognition. Importantly, this relationship held even when accounting for differences in education, chronic medical conditions, income, and age itself.

This isn’t the first time the psychological load of worry and rumination has shown up in cognitive studies. In earlier work, elevated RNT corresponded to increased subjective cognitive complaints — people felt their memory or thinking skills slipping — and this subjective decline lined up with objective markers in the brain tied to Alzheimer’s disease, like amyloid-beta and tau protein accumulation. What’s compelling about all this is that RNT is potentially modifiable. It’s not inherent aging, not purely biology. It is a pattern of thinking, and thus one where intervention could make a difference. Techniques like cognitive behavioral therapy, mindfulness training, or structured stress management could reduce the frequency or intensity of repetitive negative thoughts.

There are caveats: many studies are cross-sectional (a snapshot), making it hard to prove the thinking patterns cause decline rather than the opposite or some third factor doing both. Also, most samples aren’t fully representative globally; demographic factors like age range, education level, cultural background, and existing health conditions matter. Nonetheless, given the growing aging population worldwide, the findings suggest mental health and psychological screening should probably play a bigger role in geriatric care. Encouraging older adults to develop healthier thinking habits—perhaps fostering resiliency, gratitude, or coping strategies—may prove to be a tangible line of defense in protecting the aging brain.