In a bold move underscoring the Trump administration’s commitment to an “American nuclear renaissance,” the U.S. government has entered into a strategic partnership with Westinghouse Electric Company (via its owners Brookfield Asset Management and Cameco Corporation) to facilitate construction of at least $80 billion worth of new AP1000 legacy-nuclear reactors in the United States. According to reporting by Reuters, the government will take on financing and permitting support in exchange for a 20 % share of cash distributions exceeding $17.5 billion. Additional coverage by Barron’s notes that if Westinghouse’s valuation tops $30 billion by 2029, the government can require an IPO and secure a 20 % equity stake via warrant. Moreover, commentary from the Financial Times reveals that construction-risk remains a major sticking point: with lead builder Bechtel Group Inc. calling for risk-sharing between private contractors and the federal government because past large reactors have suffered massive cost overruns. This deal signals a substantial shift in U.S. energy strategy toward large-scale nuclear deployment as a foundational pillar for powering high-intensity loads like artificial-intelligence data centers and reinforcing the nation’s industrial and energy posture.

Sources: Reuters, Utility Dive

Key Takeaways

– The $80 billion-plus deal between the U.S. government and Westinghouse (plus Brookfield and Cameco) aims for rapid deployment of legacy large-scale nuclear reactors (AP1000 design) in the U.S. grid.

– In exchange for government support (financing and permitting), the government secures a return structure: 20 % of cash distributions beyond $17.5 billion and a potential 20 % equity stake via a warrant if valuation thresholds are met.

– Despite the ambitious scope, industry voices caution: past U.S. reactor builds (including at Plant Vogtle) reveal steep cost overruns and delays, and firms like Bechtel insist the government must share construction finance risk to make the model viable.

In-Depth

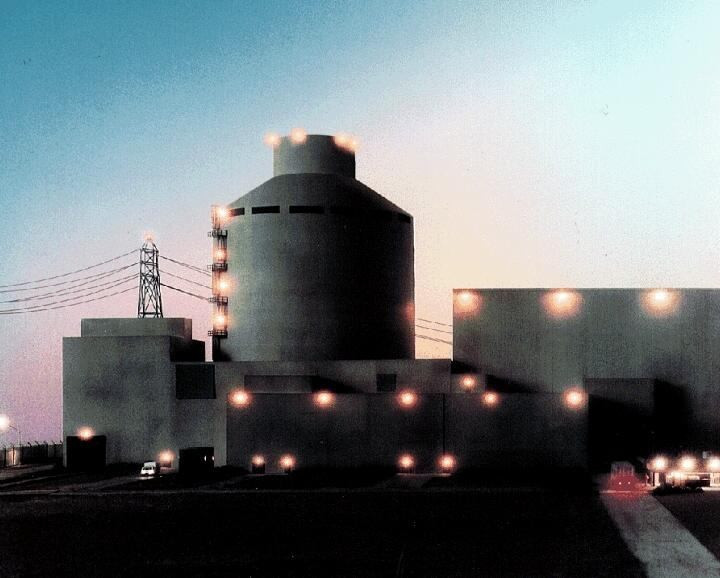

The recent announcement that the U.S. government has locked in a strategic partnership with Westinghouse Electric, Brookfield Asset Management and Cameco Corporation for the construction of at least $80 billion worth of nuclear reactors represents one of the most significant energy-policy moves in recent decades. At the heart of the deal is a return to “large-scale, legacy reactor” builds — specifically the AP1000 design developed by Westinghouse — rather than experimental next-generation reactor technologies. According to Reuters, the U.S. will provide permitting and financing support on behalf of private firms in return for a share of profits once certain thresholds are met.

Complementary reporting from Barron’s confirms that if Westinghouse goes public and is valued at more than $30 billion by January 2029, the U.S. can compel an IPO and take a 20 % stake via a warrant.

From a conservative vantage point, this deal aligns with core priorities: reinforcing American industrial capacity, reducing reliance on foreign energy imports, enhancing grid resilience, and positioning the U.S. for the data-intensive demands of artificial-intelligence and high-performance computing infrastructure. The emphasis on large baseload nuclear generation signals a recognition that renewables alone (wind/solar) will struggle to meet the scale, reliability and continuous load demands of a 21st-century digital economy.

However, the deal isn’t without risk. Industry players and observers note that nuclear-construction projects in the U.S. have historically been plagued by overruns, schedule slippage and regulatory bottlenecks. For example, the experience at Plant Vogtle in Georgia — originally projected at $14 billion and now estimated at upward of $30 billion for the two new AP1000 units — remains a cautionary tale. Critics point out that gloves off, the nuclear business demands close government-industry coordination and often requires the taxpayer to assume significant downside risk. In this context, Bechtel’s call for risk-sharing between the private sector and government (rather than the private sector bearing full cost overrun liability) is telling.

By deploying such a large magnitude of new nuclear capacity, the U.S. stands to generate tens of thousands of construction jobs and revitalize domestic heavy‐industry supply chains for reactor components, steel, fabrication and skilled labor — a vital boon for manufacturing communities across the country. Utility Dive reports the program could create more than 100,000 construction jobs.

On the financing side, while the headline figure of $80 billion is substantial, questions remain: how much of that will be direct taxpayer outlay, how much will be financed by private capital with government guarantees, and how transparent and enforceable the return-to-taxpayer mechanisms will be. The fact that the government is only guaranteed 20 % of upside beyond a return threshold suggests the private firms are structuring the risk–return profile in their favor; if the projects fail to meet the requisite returns, taxpayer exposure could be large without commensurate upside.

From a strategic standpoint, the deal also carries geostrategic dimensions: by revitalizing U.S. nuclear capability, Washington signals global leadership in advanced nuclear deployment and positions American firms to compete for export markets at a time when European projects such as the UK’s Sizewell C are seeing higher costs per gigawatt and slower progress. In effect, this investment could help the U.S. capture a larger share of the global nuclear-build market, reinforcing both energy and foreign-policy leverage.

That said, the choice to build legacy AP1000 reactors rather than more compact or modular Generation IV designs may spark debate within conservative energy circles. Proponents argue that the AP1000 is a proven design with existing licensing in the U.S. and thus represents lower technology risk. Detractors caution that the multi-billion-dollar upfront cost and long lead times remain Achilles’ heels — particularly when compared with smaller modular reactors (SMRs) or other next-gen approaches that promise faster deployment and lower capital intensity.

In the end, if executed effectively, this deal could mark a turning point in U.S. energy infrastructure — one that bolsters energy independence, stimulates manufacturing and puts the country in a stronger position for the digital-age power demands. But it will require rigorous program management, an honest accounting of taxpayer risk, and disciplined governance to ensure that the massive price tag yields commensurate benefit. The details of execution — cost control, licensing speed, supply-chain resilience, workforce readiness — will ultimately determine whether this is a triumph of conservative industrial-energy policy or another expensive lesson in nuclear project challenges.