Researchers at MIT have discovered that subtle atomic patterns—known as chemical short-range order—persist even in metals manufactured through conventional industrial methods, defying the long-standing assumption that processing fully randomizes atomic configurations. Using a combination of machine learning, molecular dynamics simulations, and statistical models, the team showed that defects in metals (dislocations) preferentially break weaker bonds in a non-random, biased way, producing nonequilibrium steady states of atomic order that cannot be predicted from traditional thermodynamic equilibrium theory. This overturns decades of theoretical assumptions and opens up a possibility for engineers to exploit these hidden patterns to tune properties such as strength, durability, heat capacity, and radiation resistance in alloys.

Sources: Science Tech Daily, MIT.edu

Key Takeaways

– Conventional metal manufacturing does not fully randomize atomic arrangements; instead, hidden chemical patterns survive processing and persist in steady nonequilibrium states.

– Dislocations—the defects in crystal lattices—play an active role in guiding atomic rearrangements by preferentially breaking weaker bonds, leading to biased chemical ordering rather than pure randomness.

– This discovery gives materials engineers a new lever to design and fine-tune alloy behaviors (e.g. strength, radiation tolerance) by manipulating processing pathways and atomic ordering, beyond just composition and microstructure.

In-Depth

This new work is a fairly dramatic shakeup in how we understand metal alloys and the atomic processes during manufacturing. For a long time, material scientists have operated under the assumption that the harsh processes involved in forming metals—heating, deformation, rolling, annealing—serve to erase any subtle atomic ordering, leaving behind essentially a random solid solution at the atomic scale. The hidden chemical motifs, thought to be irrelevant or too fragile, were mostly dismissed in industrial settings.

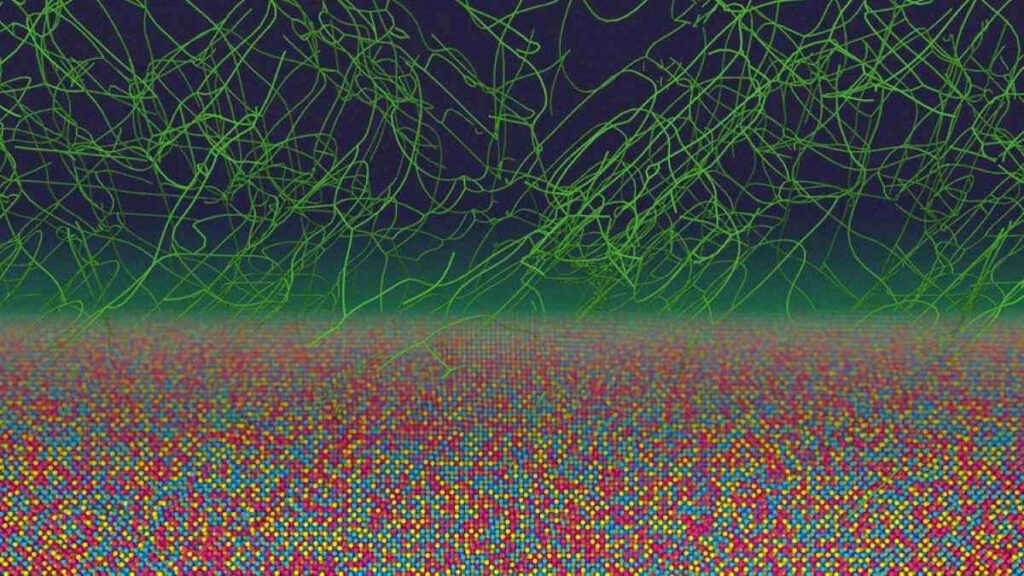

But the MIT team’s simulations and modeling show otherwise. They tracked millions of atoms under realistic processing conditions and found that chemical short-range order (SRO)—a bias in how atomic species cluster or avoid each other locally—can not only survive but reach a new kind of nonequilibrium steady state that would never be predicted by classic equilibrium thermodynamics. In short: nature in metals is not purely a fight toward maximum disorder; there is structure even in the chaos of processing.

The heart of the matter lies with dislocations—defects in the crystal lattice that accommodate deformation. These aren’t passive damage centers; they have “preferences.” As they move and shift atoms around under stress, they tend to break the weaker chemical bonds preferentially and rearrange atoms in certain favorable patterns, not at random. That bias means even a process meant to shuffle atoms can leave behind statistically biased motifs.

What’s exciting—and a little unnerving to old-school theory—is that engineers might now have a new control knob. If you can understand how processing parameters (temperature, strain rate, deformation cycles) influence atomic ordering, you could purposefully steer an alloy toward a hidden but beneficial internal structure—improving mechanical strength, resistance to radiation damage, or durability—without changing its bulk composition or average microstructure. It’s a new design dimension beyond just “what atoms are in it” and “how big are the grains.”

In a conservative framework, this finding underscores the importance of caution when extending theoretical models too far. Many predictions in alloy behavior have relied on assuming equilibrium randomness; this study warns that reality is messier, and manufacturing history can leave indelible atomic fingerprints. The work also reinforces the value of combining computational power, machine learning, and deep physics insight to challenge long-held assumptions.