Recent research digs deeper into how Earth’s South Atlantic Anomaly (SAA)—a region where Earth’s magnetic shield is unusually weak—is not only drifting and weakening, but now appears to be splitting into two distinct lobes. Scientists trace much of the effect to movements and irregularities deep in the Earth’s core: about 1,800 miles below the African continent lies what’s known as the African Large Low Shear Velocity Province, a dense region that seems to disrupt the geodynamo (the molten-iron flows generating the magnetic field). As the anomaly evolves, satellite operators are growing concerned: the splitting lobes may increase risks to space hardware, especially when satellites orbits pass through those zones. NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA) are using data from missions like ESA’s Swarm constellation and others to map these changes and refine geomagnetic models so future missions can better anticipate those effects.

Sources: Sustainability Times, European Space Agency, arXiv

Key Takeaways

– The South Atlantic Anomaly is evolving: it’s drifting northwest, weakening in strength, and currently splitting into two minima (“lobes”) of magnetic intensity.

– Deep internal Earth structure—and specifically the African large low shear velocity province—plays a key role in disrupting magnetic field generation, contributing to both the weakening and morphological change in the SAA.

– Operationally, this evolving anomaly poses rising risks for spacecraft and satellites: more exposure to solar radiation and charged particles, increased occurrence of single event upsets, and mission planning must increasingly account for these magnetic irregularities.

In-Depth

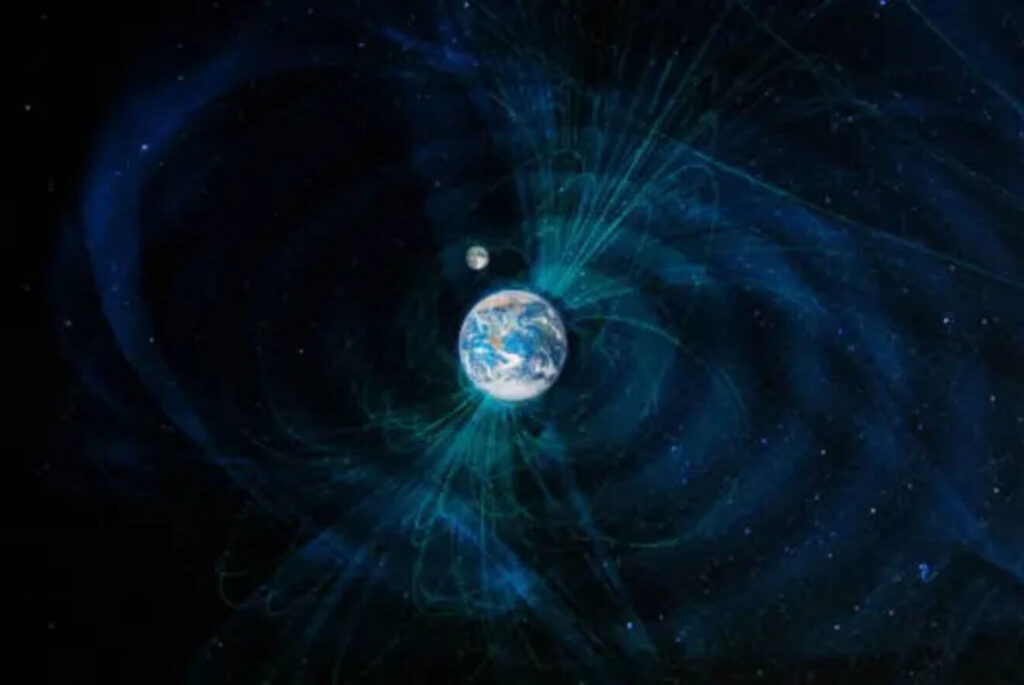

Earth’s magnetic shield is often taken for granted, the invisible force field protecting our planet from a barrage of solar radiation and cosmic particles. But over the South Atlantic Ocean and parts of South America, that shield is showing signs of serious wear—and not just in strength, but in shape. The region known as the South Atlantic Anomaly (SAA) has long been under scientific scrutiny for being weaker than surrounding areas. Now, new research indicates it’s not a simple notch but may be splitting into two lobes—two separate centers of weakest magnetic field—each with their own risks attached.

At the heart of this change is Earth’s geodynamo: molten iron and nickel swirling in the outer core generate most of our planet’s magnetic field. But that process isn’t uniform. Beneath Africa, approximately 1,800 miles down, lies a region called the African large low shear velocity province (LLSVP). This dense mantle structure seems to interfere with the flow patterns in the core and disrupt how the field is generated above. Also, the tilt between Earth’s magnetic and rotational axes exacerbates the issue, producing anomalies in field strength.

Satellite data—especially from ESA’s Swarm missions—is key in tracking how weak the SAA is becoming, how it’s shifting westward or northwestward, and how one of its centers of minimum magnetic strength has developed southwest of Africa. What’s striking is that the secondary center isn’t just a theoretical projection: it is already showing in the data. This has scientists recalibrating their geomagnetic models (like CHAOS-7) to account for multiple minima rather than a single dip.

For spacecraft and satellite operators, this is not just academic. The SAA exposes satellites to higher levels of harmful charged particles, raising the risk of single-event upsets—temporary or permanent malfunctions caused by high-energy protons or other particles. Even the International Space Station traverses parts of the anomaly. As the SAA evolves—splitting lobes, drifting motion—the zones of risk change. That means more complex planning, possibly more shielding, and better forecasting of when and where spacecraft will encounter weak-magnetic-field zones.

In the larger picture, the evolution of the SAA also tells us something about Earth itself: the deep interior is far from static. Mantle and core interactions, variations in flow, and heterogeneities beneath continents—all that stuff hidden deep off-limits to direct observation—are influencing phenomena we can track from space. And while there’s no indication that this anomaly signals an imminent magnetic pole reversal (which tends to unfold over many thousands of years), it does sharpen the need for vigilance. As our reliance on satellites, telecommunications, and space infrastructure grows, so does the imperative to understand and adapt to changes in Earth’s magnetic environment.