Swedish researchers from Linköping University have unveiled two cutting-edge 3D bioprinting technologies that generate artificial skin capable of supporting bloodflow, a milestone in regenerative medicine. The team developed a bio-ink dubbed “μInk,” which suspends fibroblasts (cells that build up connective tissue) on gelatin microspheres within a hyaluronic acid gel, and used it to print thick, cell-dense skin tissue. In mice, this printed tissue not only grew living cells producing collagen and other dermal components, but also developed new blood vessels. The second technology—REFRESH (Rerouting of Free-Floating Suspended Hydrogel Filaments)—constructs hydrogel threads that act as temporary scaffolds: they can be tied, braided, maintain shape memory, and later be dissolved enzymatically to leave behind channels that mimic blood vessels. While there’s promise, challenges like infection risk, immune response, and scaling to human use remain.

Sources: Linköping University, Wired, TechSpot

Key Takeaways

– The integration of vascularization (i.e. forming blood vessel networks) into artificial skin is a significant leap forward: without it, thicker skin constructs fail to deliver oxygen/nutrients to all cells, and central areas die off.

– The two technologies developed—μInk and REFRESH—play complementary roles: μInk provides dense, living dermal tissue; REFRESH makes customizable vessel-like channels that can later be removed to allow bloodflow.

– Moving from animal models to safe, effective human clinical applications is a non-trivial path: immune reactions, infection, mechanical stability, full integration (with nerves, appendages, etc.), and manufacturing at scale are obstacles still to be addressed.

In-Depth

Regenerative medicine has long grappled with the difficulty of recreating full-functioning skin—not just its superficial layer, but the deeper dermis, replete with blood vessels and the complex support structures that make skin a living, responsive organ.

Severely burned or traumatically injured patients often receive grafts that restore the epidermis, but the lack of proper dermal regeneration means persistent scarring, loss of function, and cosmetic issues. A promising fresh front in this struggle has arrived courtesy of researchers at Linköping University in Sweden, who have successfully demonstrated that artificial skin can be printed with built-in capacity for vascularization—an achievement that may change how serious skin injuries are treated.

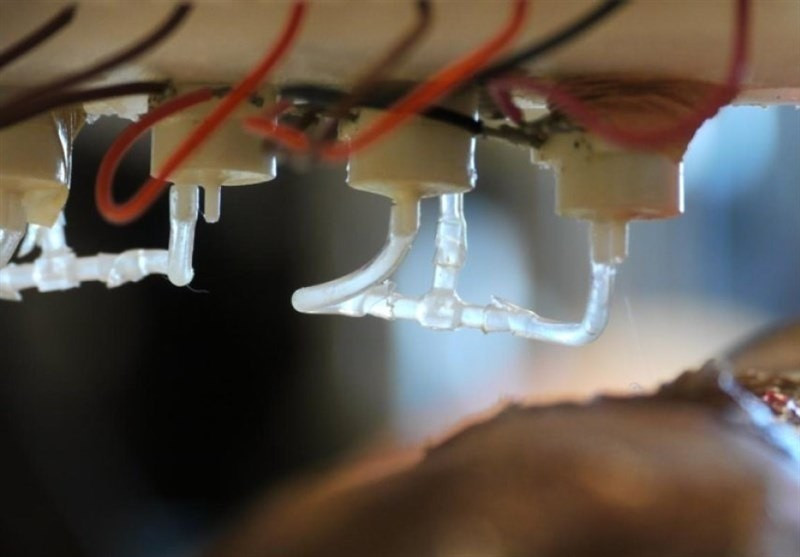

Two distinct but complementary technologies lie at the heart of this advance. First is μInk, a bio-ink that uses fibroblasts seeded on spongy gelatin spheres and held within a hyaluronic acid gel. Fibroblasts are critical: they produce collagen, elastin, hyaluronic acid—all the building blocks of the dermis. Using μInk and 3D printing, the team constructed skin-like tissues densely packed with living cells; when transplanted into mice, these constructs produced collagen and reassembled meaningful dermal structure, with new blood vessels growing in. The second technology, REFRESH, focuses more directly on vascular architecture. It prints hydrogel filaments that can be shaped (knots, braids, etc.), hold form under stress, and later be enzymatically removed, leaving voids that act like channels. These become templates for capillary networks when integrated into tissue.

Together, μInk and REFRESH offer a path toward artificial skin that does more than cover wounds—it can potentially replace lost dermis, support blood flow, enable nutrition and oxygen delivery throughout the tissue, thus making the graft more robust, healthier, and more functional. But the road ahead is still long. Experiments in mice are promising but do not fully mimic the human immune system, infection risk, or the mechanical stresses skin undergoes in real life. Scaling up—both in size of grafts and production processes—will also be challenging. Moreover, integrating nerves, hair follicles, pigment, and other skin features remains a hurdle. Finally, regulatory, ethical, and cost barriers will shape how fast such technology reaches patients.

This is one of those rare scientific achievements that seems less like speculative science fiction and more like the beginning of viable clinical translation. If the remaining technical and safety challenges can be solved, we may be moving toward grafts that restore both form and function far better than what’s possible today.