UCLA and UC Riverside researchers have developed a physics-inspired computing prototype—an “Ising machine” that uses a network of synchronized oscillators instead of digital bits to tackle hard combinatorial optimization tasks at room temperature. The device leverages quantum-material properties of tantalum sulfide to couple electrical signals with atomic vibrations, enabling parallel computation with greater energy efficiency and compatibility with existing silicon technologies. Their findings, published in Physical Review Applied, promise a low-power alternative to traditional and cryogenic quantum systems and open pathways toward integrating such hardware into CMOS-based platforms.

Sources: SciTechDaily, Deep Tech Bytes, DQ

Key Takeaways

– Room-Temperature Operation: The oscillator-based architecture solves complex tasks without requiring cryogenic cooling, a typical hurdle for quantum systems.

– Energy-Efficient & Scalable: The design offers potentially lower power consumption and works toward easy integration with current silicon chip manufacturing.

– Quantum-Informed, Classical-Compatible: Utilizing tantalum sulfide, the technology merges quantum phenomena with classical CMOS infrastructure to deliver enhanced computation for real-world applications.

In-Depth

In an era when computing bottlenecks and soaring energy demands weigh heavily on innovation, the UCLA-UC Riverside team has introduced a fresh take on solving some of the most difficult optimization problems—those that are essential to logistics, network design, and AI training.

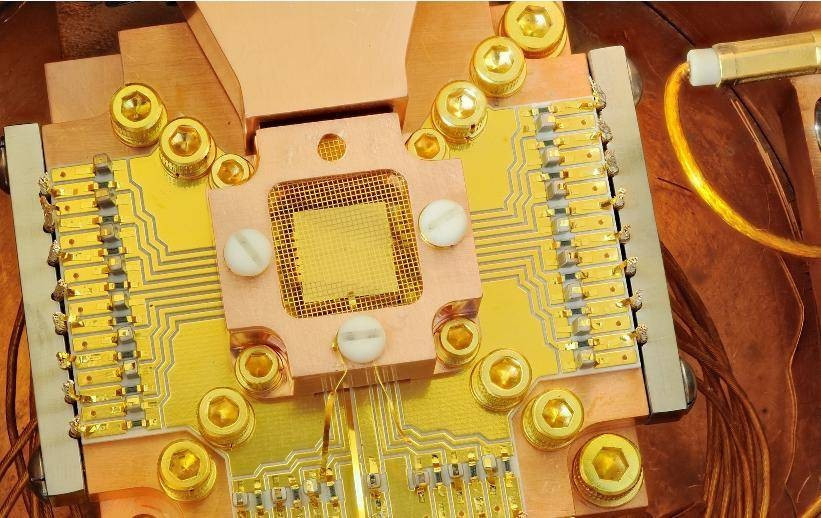

By foregoing binary bits and embracing a physics-inspired paradigm—an oscillator network known as an Ising machine—they let the system “naturally” sync up to a solution. That synchronization happens thanks to quantum behaviors embedded in a special form of tantalum sulfide, a material that links electrical charge with atomic vibrations. Published in Physical Review Applied, their proof-of-concept works at everyday room temperature, sidestepping the energy-intensive cooling demanded by most quantum machines. It’s a practical approach, striking at the heart of what chips—both classical and quantum—need to become: efficient, scalable, and ready to plug into the silicon economy.

The speculative leap this represents is twofold: first, it signals a shift from strictly digital logic to computation grounded in physical phenomena; second, it takes us closer to hybrid systems that blend tried-and-true CMOS tech with quantum-informed hardware. As Professor Alexander Balandin and his collaborators argue, any new computing hardware will need to coexist with current infrastructure to make an actual difference—and this oscillator design could do just that.

With funding from the Office of Naval Research and Army Research Office backing its potential for real-world deployment, the project may signal a turning point—where energy-efficient, parallel computation becomes standard in tackling complex challenges that underpin everything from supply chains to AI workflows.